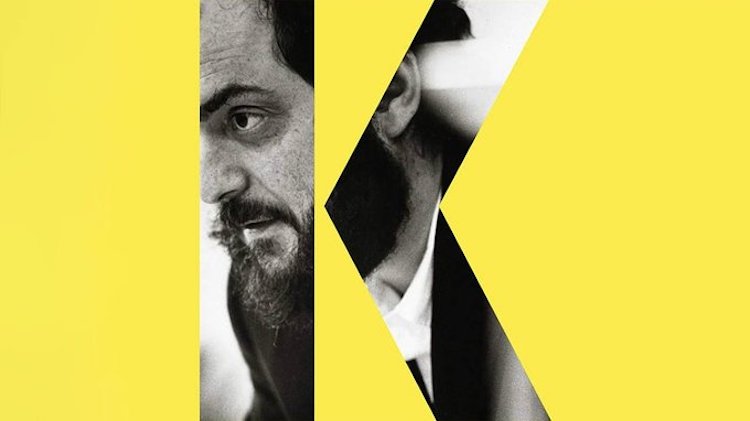

Two rival biographies of Stanley Kubrick were published almost simultaneously in 1997. John Baxter and Vincent LoBrutto’s books were both unauthorised accounts, though LoBrutto’s was considerably more accurate than Baxter’s. They are now joined by a third major Kubrick biography, Nathan Abrams and Robert P. Kolker’s Kubrick: An Odyssey, which was released earlier this year.

The previous biographies were published before the release of Eyes Wide Shut—the subject of another Abrams and Kolker book—making Kubrick the first biography to cover the director’s entire career. (The authors previously dismissed Eyes Wide Shut’s state of incompletion at the time of Kubrick’s death as “ultimately irrelevant”, though in their biography they take it more seriously, calling it “the most serious controversy of Kubrick’s career”.

The previous biographies were published before the release of Eyes Wide Shut—the subject of another Abrams and Kolker book—making Kubrick the first biography to cover the director’s entire career. (The authors previously dismissed Eyes Wide Shut’s state of incompletion at the time of Kubrick’s death as “ultimately irrelevant”, though in their biography they take it more seriously, calling it “the most serious controversy of Kubrick’s career”.

Kubrick is particularly significant as the first biography based on material from the Kubrick Archive, making it more reliable than its predecessors. When Kolker and Abrams occasionally veer into speculation, though (“perhaps...”), they are on shakier ground, and their regular references to the significance of Kubrick’s Jewish identity (a thesis developed by Abrams) feel forced.

Kolker and Abrams are also the first Kubrick biographers to receive cooperation from the director’s family. The book benefits substantially from this level of access, but it’s also a double-edged sword: Kubrick’s brother-in-law, Jan Harlan, who acted as a liason, sometimes attempted to steer the authors in directions that contradicted their own research. (All the writers can do is to ask rhetorically, “as with so much in Kubrick’s life, which version is true?”)

Kubrick has a bibliography and a comprehensive index, but there are no footnotes, and quotes often appear in the text without attribution. This makes it needlessly difficult to identify the sources of quotations, beyond those that are familiar from other publications. (Kubrick joins more than sixty other Kubrick books on the Dateline Bangkok bookshelves.)

Kolker and Abrams are also the first Kubrick biographers to receive cooperation from the director’s family. The book benefits substantially from this level of access, but it’s also a double-edged sword: Kubrick’s brother-in-law, Jan Harlan, who acted as a liason, sometimes attempted to steer the authors in directions that contradicted their own research. (All the writers can do is to ask rhetorically, “as with so much in Kubrick’s life, which version is true?”)

Kubrick has a bibliography and a comprehensive index, but there are no footnotes, and quotes often appear in the text without attribution. This makes it needlessly difficult to identify the sources of quotations, beyond those that are familiar from other publications. (Kubrick joins more than sixty other Kubrick books on the Dateline Bangkok bookshelves.)