Rupert Murdoch—proprietor of The Sun, The Times, and Fox News—ran his media empire for more than seventy years, before finally retiring aged ninety-two. Murdoch was an endling, the last surviving member of an endangered (and now extinct) species: the press baron. He announced his retirement on 21st September, less than a week before the publication of a new book on the twilight of his career, which will be released tomorrow.

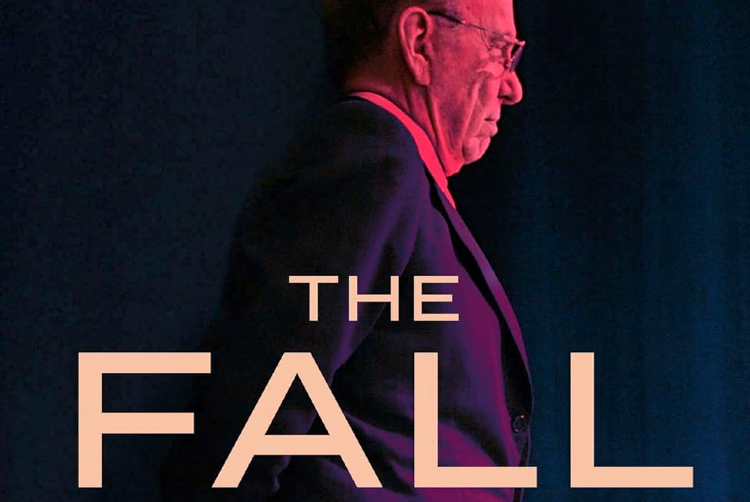

The UK edition of Michael Wolff’s book is titled The Fall: The End of the Murdoch Empire, and little did the author know how prescient that subtitle would be. (In the US, the subtitle is The End of Fox News and the Murdoch Dynasty.) This is Wolff’s second book on Murdoch: he previously wrote The Man Who Owns the News, an excellent biography that benefited from rare access to Murdoch himself and his immediate family.

As Wolff writes in his introduction to The Fall, “Murdoch hated my book about him,” so this second volume is an unauthorised account. But Wolff still has contacts close to Murdoch, explaining that this makes him “the journalist not in his employ who knows him best.” (This is actually rather modest for Wolff, who boasted in a November 2011 GQ article about Murdoch: “I know what he is thinking; I know how he is thinking it; I know the rhythms of the way he talks about what he thinks; I know what he remembers and I know what he forgets.”)

After that first Murdoch biography, Wolff wrote a series of books on Donald Trump’s presidency, starting with Fire and Fury, which relied for many of its revelations on Steve Bannon, Trump’s former chief political strategist. Wolff similarly uses former Fox News chief executive Roger Ailes as a major source in The Fall. The problem this time, though, is that Ailes resigned in disgrace in 2016, and died a year later. Despite this, The Fall is padded out with a prologue on Ailes, who Wolff still seems to admire.

The Man Who Owns the News contained extensive notes on its sources, but The Fall has no notes whatsoever. And while it’s become standard practice for writers of contemporary history to cite unidentified sources, Wolff goes a step further: often, he doesn’t even refer to individual sources, whether anonymous or otherwise. Also, Wolff didn’t approach Fox News to verify what he had written, breaking a basic rule of journalism. Then again, as he explains in his introduction, he sees himself as “a writer, perhaps more so than as strictly a journalist”.

This results in a book with plenty of colour but little evidence. Wolff adds novelistic details to his dialogue, telling us not only what the participants said, but also how they said it, how they felt, and even their body language at the time. He quotes Murdoch’s concerns about the Dominion Voting Systems defamation case, for instance: “quietly, but clearly” Murdoch said that the lawsuit “could cost us fifty million dollars”. Later in the same conversation—on Murdoch’s yacht—the tycoon banged a table, grumbled, scowled, and felt affronted. How Wolff knows all this is anyone’s guess.

Murdoch’s prediction of the Dominion payout was a gross underestimate, as Fox ended up paying almost $800 million for broadcasting Trump’s lies about election fraud. Wolff was in the courtroom when the judge announced that Fox had settled the case, and he reveals that Murdoch originally proposed firing host Sean Hannity as part of the settlement. (Ultimately, Tucker Carlson was sacked instead.)

Another of Wolff’s stylistic devices is to distance himself from the narrative, to an extent that sometimes misleads the reader. In Fire and Fury, he wrote that Trump telephoned an “acquaintance” without revealing that the acquaintance was Wolff himself. Likewise, in The Fall, he describes Ailes speaking to an “interlocutor” without disclosing that he was almost certainly the interlocutor in question. (He has also done this in recent interviews, with an anecdote about Murdoch, Trump, and a “guest” in a lift. In some interviews, he has identified himself as the guest, though in others he leaves the guest unnamed.)

When Murdoch retired last week—an event that Wolff did not foresee—he confirmed that his son Lachlan would take over as executive chairman. (As in the HBO series Succession, the long-term heir will only be determined once Murdoch dies.) In light of that announcement, Wolff’s reading of their relationship now seems off beam: “he seemed to wholly disregard whatever Lachlan might say. Could it be that the father had had it with the son?” It’s a rhetorical question, but the answer is apparently ‘no’.

The UK edition of Michael Wolff’s book is titled The Fall: The End of the Murdoch Empire, and little did the author know how prescient that subtitle would be. (In the US, the subtitle is The End of Fox News and the Murdoch Dynasty.) This is Wolff’s second book on Murdoch: he previously wrote The Man Who Owns the News, an excellent biography that benefited from rare access to Murdoch himself and his immediate family.

As Wolff writes in his introduction to The Fall, “Murdoch hated my book about him,” so this second volume is an unauthorised account. But Wolff still has contacts close to Murdoch, explaining that this makes him “the journalist not in his employ who knows him best.” (This is actually rather modest for Wolff, who boasted in a November 2011 GQ article about Murdoch: “I know what he is thinking; I know how he is thinking it; I know the rhythms of the way he talks about what he thinks; I know what he remembers and I know what he forgets.”)

After that first Murdoch biography, Wolff wrote a series of books on Donald Trump’s presidency, starting with Fire and Fury, which relied for many of its revelations on Steve Bannon, Trump’s former chief political strategist. Wolff similarly uses former Fox News chief executive Roger Ailes as a major source in The Fall. The problem this time, though, is that Ailes resigned in disgrace in 2016, and died a year later. Despite this, The Fall is padded out with a prologue on Ailes, who Wolff still seems to admire.

The Man Who Owns the News contained extensive notes on its sources, but The Fall has no notes whatsoever. And while it’s become standard practice for writers of contemporary history to cite unidentified sources, Wolff goes a step further: often, he doesn’t even refer to individual sources, whether anonymous or otherwise. Also, Wolff didn’t approach Fox News to verify what he had written, breaking a basic rule of journalism. Then again, as he explains in his introduction, he sees himself as “a writer, perhaps more so than as strictly a journalist”.

This results in a book with plenty of colour but little evidence. Wolff adds novelistic details to his dialogue, telling us not only what the participants said, but also how they said it, how they felt, and even their body language at the time. He quotes Murdoch’s concerns about the Dominion Voting Systems defamation case, for instance: “quietly, but clearly” Murdoch said that the lawsuit “could cost us fifty million dollars”. Later in the same conversation—on Murdoch’s yacht—the tycoon banged a table, grumbled, scowled, and felt affronted. How Wolff knows all this is anyone’s guess.

Murdoch’s prediction of the Dominion payout was a gross underestimate, as Fox ended up paying almost $800 million for broadcasting Trump’s lies about election fraud. Wolff was in the courtroom when the judge announced that Fox had settled the case, and he reveals that Murdoch originally proposed firing host Sean Hannity as part of the settlement. (Ultimately, Tucker Carlson was sacked instead.)

Another of Wolff’s stylistic devices is to distance himself from the narrative, to an extent that sometimes misleads the reader. In Fire and Fury, he wrote that Trump telephoned an “acquaintance” without revealing that the acquaintance was Wolff himself. Likewise, in The Fall, he describes Ailes speaking to an “interlocutor” without disclosing that he was almost certainly the interlocutor in question. (He has also done this in recent interviews, with an anecdote about Murdoch, Trump, and a “guest” in a lift. In some interviews, he has identified himself as the guest, though in others he leaves the guest unnamed.)

When Murdoch retired last week—an event that Wolff did not foresee—he confirmed that his son Lachlan would take over as executive chairman. (As in the HBO series Succession, the long-term heir will only be determined once Murdoch dies.) In light of that announcement, Wolff’s reading of their relationship now seems off beam: “he seemed to wholly disregard whatever Lachlan might say. Could it be that the father had had it with the son?” It’s a rhetorical question, but the answer is apparently ‘no’.