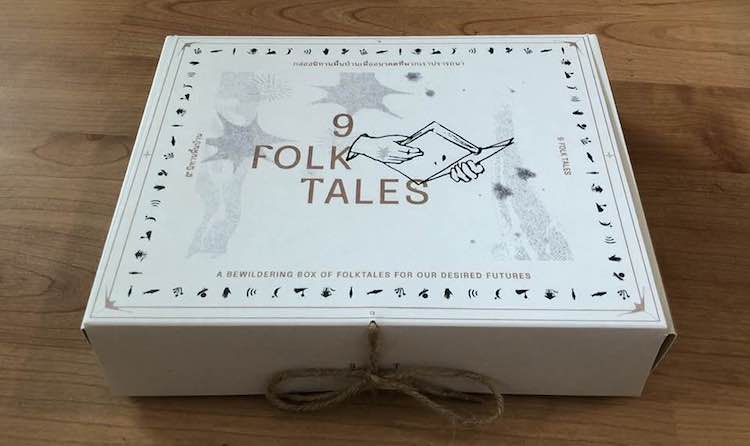

Are children’s stories traditional or old-fashioned? Do they teach age-old values or foster outdated stereotypes? Could they even have a propagandist function, promoting conformity and obedience? The editors of Nine Folk Tales have commissioned nine new versions of classic folk tales to subvert the narratives that children are usually spoon-fed, and to encourage critical thinking. Rubkwan Thammaboosadee and Palin Ansusinha have produced a box set of revisionist folk tales, drawing on examples from Aesop’s fables, the Brothers Grimm, and several traditional Thai tales. In Eat Your Stories (กินเรื่องราว), their reader’s guide to the collection, they argue that these familiar fables “teach us to stay within the moral framework ruled by social inequality.” In a nutshell, the objective of their updated folk tales is to “dismantle old tales by telling new ones”.

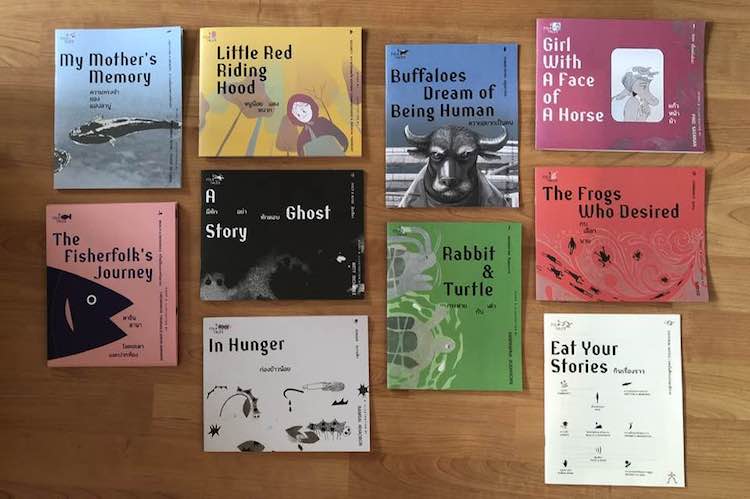

The new folk tales are allegories that promote social and economic equality, justice, and freedom. The nine books are: The Frogs Who Desired (กบเลือกนาย) by Narsid, My Mother’s Memory (ความทรงจำของแม่ปลาบู่) by Thiptawan Uchai, Girl with a Face of a Horse (แก้วหน้าม้า) by Ping Sasinan, In Hunger (ก่องข้าวน้อย) by Namsai Khaobor, The Fisherfolk’s Journey (ตาอินตานา โชคชะตาและปากท้อง) by Laksanapon Tarapan and Wiriya Wiriyapat, Rabbit and Turtle (กระต่ายกับเต่า) by Sanprapha V., A Ghost Story (ผีทักอย่าทักตอบ) by Arty Nicharee, Buffaloes Dream of Being Human (ควายอยากเป็นคน) by Tepwut Buatoom, and Little Red Riding Hood (หนูน้อยหมวกแดง) by Rubkwan Thammaboosadee.

The new folk tales are allegories that promote social and economic equality, justice, and freedom. The nine books are: The Frogs Who Desired (กบเลือกนาย) by Narsid, My Mother’s Memory (ความทรงจำของแม่ปลาบู่) by Thiptawan Uchai, Girl with a Face of a Horse (แก้วหน้าม้า) by Ping Sasinan, In Hunger (ก่องข้าวน้อย) by Namsai Khaobor, The Fisherfolk’s Journey (ตาอินตานา โชคชะตาและปากท้อง) by Laksanapon Tarapan and Wiriya Wiriyapat, Rabbit and Turtle (กระต่ายกับเต่า) by Sanprapha V., A Ghost Story (ผีทักอย่าทักตอบ) by Arty Nicharee, Buffaloes Dream of Being Human (ควายอยากเป็นคน) by Tepwut Buatoom, and Little Red Riding Hood (หนูน้อยหมวกแดง) by Rubkwan Thammaboosadee.

Buffaloes Dream of Being Human

Some of the tales have political subtexts, the most overt being Buffaloes Dream of Being Human, a fable in which a group of buffaloes seek a better life in the big city. In Thai, kwai (‘buffalo’) is an insult aimed at poor voters, especially those who supported former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra. (Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s video Silence addresses this pejorative, and it has been reclaimed by some pro-democracy protesters.) The story includes thinly-veiled references to Thaksin—“Monkey, a friend of the buffalo, was elected as the city’s governor”—and the yellow-shirt protests that paved the way for his removal from office: “A mob of the ‘Louder Voices’ expelled Monkey from the city.” Similarly, Charuphat Petcharavej’s short story Hakom (ห่าก้อม) also features a proxy for Thaksin: “A group of villagers had driven him out of the village”.

My Mother’s Memory

Another book in the set, My Mother’s Memory, indirectly confronts the violence suffered by the Octobrist generation in the 1970s. This disturbing tale ends with the young protagonist’s realisation: “the nightmares that I had were the result of me swimming in memories of the past. The memories of people who I might not even know. I have been carrying these heavy memories all this time.” As the editors explain in their reader’s guide, these collective memories of state violence are whitewashed from history: “Our emotions and memories carry alternative histories which are not written or taught in school history books.” (This theme of state whitewashing has been explored by numerous artists and writers, including Vasan Sitthiket, Tawan Wattuya, Sutee Kunavichayanont, Sirisak Saengow, Prabda Yoon, Thongchai Winichakul, and Emma Larkin.)

The Frogs Who Desired

If Buffaloes Dream of Being Human and My Mother’s Memory reflect the experiences of previous generations of pro-democracy protesters, The Frogs Who Desired is an allegory for the students who are currently protesting for political reform. Based on Aesop’s fable The Frogs Who Desired a King—which is itself a pertinent cautionary tale about absolute power—The Frogs Who Desired ends with the slogan “NO GODS OR ANY RULERS SHALL SAVE US, EXCEPT OURSELVES”, a paraphrase of the student protesters’ motto ‘no god, no king, only human’.

The editors point out that The Frogs Who Desired has a “purposefully shortened title”, which was presumably an ideological decision rather than a legal concern. Another book in the series, In Hunger, features a poor farmer who recalls that “a stranger with a cruel smile preached us to stay humble”. Like Buffaloes Dream of Being Human, In Hunger challenges this notion that the poor must gratefully accept their lot in life, which the editors describe as a “mechanism that keeps everyone ‘in their place’.” (Precisely the same argument is made in relation to the ‘sufficiency economy’ philosophy in Saying the Unsayable.)

Nine Folk Tales is the latest of several children’s picture books with political themes. Last year, Suwicha’s สมุดระบายสีเสรีภาพ (‘freedom colouring book’) featured a symbolic blue elephant. There have also been two sets of picture books published by Family Club and the Mirror Foundation that feature similar political allegories. This recent trend began in Hong Kong, with the Sheep Village (羊村) series, the publishers of which were jailed last year.

The editors point out that The Frogs Who Desired has a “purposefully shortened title”, which was presumably an ideological decision rather than a legal concern. Another book in the series, In Hunger, features a poor farmer who recalls that “a stranger with a cruel smile preached us to stay humble”. Like Buffaloes Dream of Being Human, In Hunger challenges this notion that the poor must gratefully accept their lot in life, which the editors describe as a “mechanism that keeps everyone ‘in their place’.” (Precisely the same argument is made in relation to the ‘sufficiency economy’ philosophy in Saying the Unsayable.)

Nine Folk Tales is the latest of several children’s picture books with political themes. Last year, Suwicha’s สมุดระบายสีเสรีภาพ (‘freedom colouring book’) featured a symbolic blue elephant. There have also been two sets of picture books published by Family Club and the Mirror Foundation that feature similar political allegories. This recent trend began in Hong Kong, with the Sheep Village (羊村) series, the publishers of which were jailed last year.